India is a land of profound cultural heritage, ancient traditions, and deep-rooted mysticism. Among the numerous deities, rituals, and folklore that shape its religious and spiritual landscape, one powerful narrative that has resonated through centuries is that of Dakini and Yogini. For those of us raised in Bengal, the imagery of these two figures—often seen beside the fierce goddess Maa Kali—stirs a mix of awe and fear. The intense portrayal of Dakini and Yogini in popular culture, especially during festivals like Kali Puja, evokes a visceral reaction, heightened by stories of tantra and witchcraft. Yet, behind this terrifying depiction lies a rich and intricate history, one that connects ancient Indian traditions with broader spiritual movements across Asia.

The Fearsome Dakini and Yogini: Who Are They?

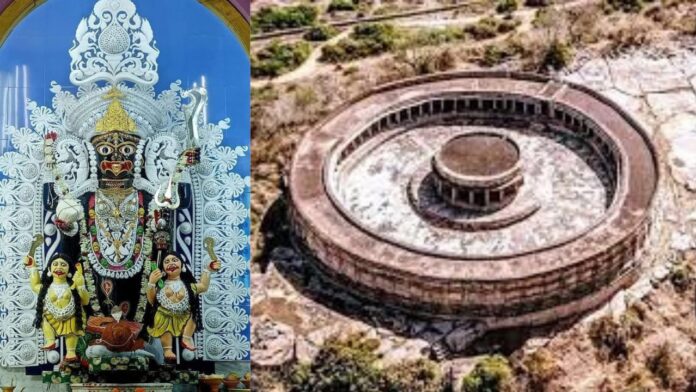

Dakini and Yogini are not merely attendants to Kali; their origins and symbolism are rooted in esoteric practices that transcend time and geography. The term Yogini refers to women who were adept practitioners of Yoga Shastra, the ancient discipline of yoga in the Hindu tradition. These women, revered for their spiritual knowledge, were part of a larger sisterhood of yogic practitioners. Over time, they became embodiments of feminine power, wisdom, and transformation. In both Hindu and Buddhist traditions, the Yoginis were believed to possess supernatural powers and were often depicted as free-spirited, independent women who challenged societal norms.

In contrast, the term Dakini comes from the Tibetan word Dak, meaning “knowledge.” Dakini are often viewed as enlightened female beings, representing wisdom in Tibetan Buddhism. Historically, Dakinis emerged as part of the Vajrayana tradition, a tantric form of Buddhism that flourished in Tibet and India during the Pala period (8th–12th centuries). Like Yoginis, Dakinis were also seen as protectors and guides in spiritual journeys, but their association with tantric practices often led to a more fearsome portrayal.

The depiction of Dakini and Yogini as attendants to the fierce goddess Kali stems from these tantric traditions. While Kali represents the destructive and transformative force of time, Dakini and Yogini serve as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual realms, guiding devotees towards deeper knowledge and liberation. Despite their terrifying outward appearances, their essence is rooted in wisdom and enlightenment.

Tantra, Witchcraft, and Misunderstandings

Over time, the imagery of Dakini and Yogini became intertwined with ideas of witchcraft and dark magic, especially in popular folklore. During festivals, pandals would compete to create the most terrifying depictions of these two figures, heightening the sense of fear surrounding their worship. However, these portrayals often overlook their original spiritual significance. While tantra—especially its darker, misunderstood aspects—does play a role in their worship, it is important to remember that tantra is, at its core, a spiritual path aimed at awakening the divine feminine within.

Historically, the association of Dakini and Yogini with witchcraft led to societal fears of witch hunts and persecution. In medieval times, women suspected of practicing witchcraft were often burned at the stake, a practice that, while not widespread in India, occurred in parts of Europe and Asia. In many ways, the misunderstood representation of these powerful female figures mirrored the larger societal fear of independent women and their connection to spiritual or mystical practices.

The Sixty-Four Yogini Temples: Guardians of the Sacred Feminine

Temples dedicated to the sixty-four Yoginis (Chausath Yogini) can still be found in a few places in India. These temples, built between the 9th and 12th centuries, were centers of tantric worship. One of the most famous is the Chaushathi Yogini Temple in Morena district, Madhya Pradesh, constructed by King Devpal of the Kachhapghat dynasty between 1055 and 1075 AD. The temple, circular in structure, houses sixty-four statues of Yoginis, each representing a different aspect of feminine power. These temples served as hubs for spiritual and tantric practices, focusing on the worship of the divine feminine.

The number sixty-four holds special significance in tantric cosmology, representing the different manifestations of divine feminine energy. While these temples were originally centers of intense spiritual practice, over time, they fell into disuse and neglect, their significance forgotten by many. Today, they stand as reminders of a time when the sacred feminine was worshipped in all its forms—both fierce and benevolent.

Edwin Lutyens and the Chaushathi Yogini Temple Connection

In a curious twist of history, the architectural legacy of the Chaushathi Yogini Temple resurfaced during the early 20th century, when the British architect Sir Edwin Lutyens was designing New Delhi’s famous architecture. Lutyens, renowned for his monumental structures, is best known for his work on the design of the Rashtrapati Bhavan (the Presidential Palace of India) and other key buildings in New Delhi. During his time in India, Lutyens traveled extensively, including to Madhya Pradesh, where he is believed to have visited the Chaushathi Yogini Temple in Morena.

Historians have long noted the striking similarity between Lutyens’ architectural designs and the structure of the Yogini temples. In particular, the circular layout of the Chaushathi Yogini Temple mirrors elements found in Lutyens’ designs for some of New Delhi’s most iconic buildings. While Lutyens was praised for his novel architectural style, many Indian historians recognized the influence of the ancient Yogini temples on his work.

The Eternal Legacy of Dakini-Yogini in Bengal

In Bengal, the worship of Yogini continues in the form of Tara Devi, especially during the Pala period when Vajrayana Buddhism flourished. Tara, like Dakini, represents wisdom and protection and is often seen as a more benevolent form of the fearsome goddess Kali. As Bengal transitioned from Buddhist to Hindu practices, many of these tantric elements were absorbed into mainstream worship, including in festivals like Kali Puja.

Even today, in many Kalipiths (temples dedicated to Kali), a stone block is kept in the sanctum sanctorum as a totem of ancient energy, symbolizing the connection to the earth and the primal forces of nature. This practice likely dates back to pre-Vedic times, when the worship of natural elements and stones was common among the indigenous people of the subcontinent.

Conclusion: A Timeless Connection to the Divine Feminine

The more one delves into the history and symbolism of Dakini and Yogini, the more one uncovers the rich and complex traditions that define Indian spirituality. These fierce yet wise feminine figures remind us of a time when the divine feminine was revered in all its forms. In Bengal, where Kali Puja remains one of the most important religious festivals, the presence of Dakini and Yogini serves as a testament to the ancient and evolving cultural heritage we continue to carry forward.

For modern-day devotees and students of Indian history alike, the study of these figures opens up new pathways of understanding—not just of the divine feminine, but of India’s long-standing tradition of blending spirituality with everyday life.